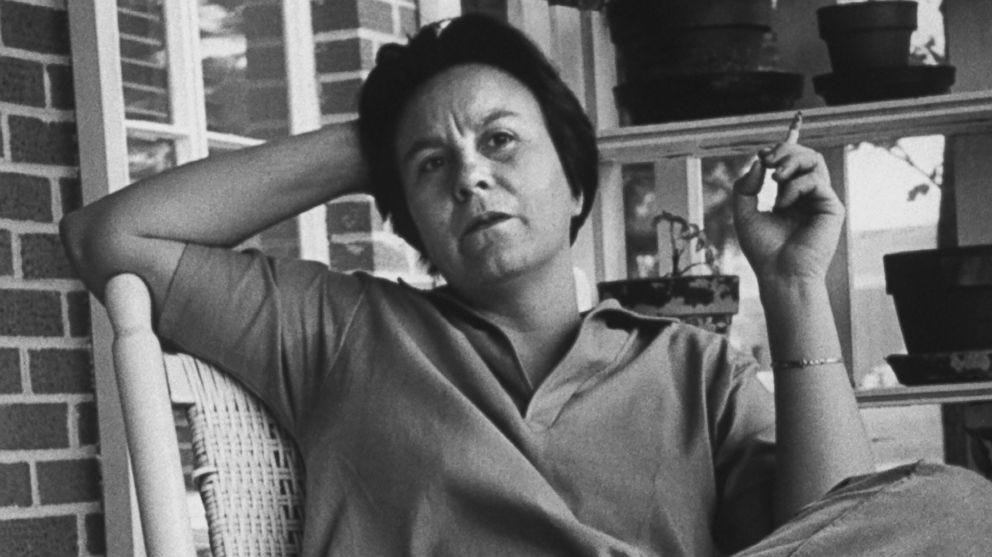

At the end of last year, I saw and almost habitually reposted this screencap-of-a-tweet about the best Christmas gift of Harper Lee’s life (presumably):

People replied: “That’s incredible!” “I wish!” and honestly, me too. A secret, stupidly optimistic part of me posted just on the off-chance that one of my limited number of Instagram followers would be like “oh, great idea” and simply venmo me $50,000 (newsletter readers: feel free!), but another part of me, I want to say knows better, or rather knows differently. Not just about the availability of $50k getting thrown about like loose change, but also about what that money means or does. The thing that this tweet gets at, the thing that I’ve been thinking about is this idea of time and space, and it being a gift, and it always having to come in these big kind of grand gestures. I think I’ve been stuck on it in some ways because I had it (sort of) and now I don’t (sort of) and I don’t know how to feel about either. But first, let’s get back to Harper Lee’s Christmas.

There are two parts to the gift, two parts to the myth. The first is the year of financial support, the time. When this gift was given, Lee was living in New York, working at an airline ticket counter and more or less spinning her wheels. What would it be like, then, if she didn’t have to ride the subway all the way out to god-knows-what corner of Queens every day, handling then-immense sums of money and watching other people on their way to places when she was stuck in New York. I am guessing she was doing a lot of the thing that I do, which is to say, complaining that if only xyz was true (she had more time, she had more space, she didn’t have that goddamn commute) maybe she would be able to write more, to actually turn and face this little itch at the corner of her brain, to sit down with the words that kept whispering past. I know that feeling well, have been trapped in that cycle of if only.

I think all the time of that Alexander Chee essay, “Impostor” which orginally ran in Catapult (R.I.P.) but was reprinted in his book, How to Write an Autobiographical Novel. In it, there’s the miracle of a cheap apartment in a lovely part of New York, Chloë Sevigny as a neighbor, and financial windfall—a kind of secret fairytale just for writers. And here are the lines I think about all the time:

I think writers are often terrifying to normal people—that is to nonwriters in a capitalist system—for this reason: there is almost nothing they will not sell in order to have the time to write. Time is our mink, our Lexus, our mansion. In a room full of writers of various kinds, time is probably the only thing that provokes widespread envy, more than acclaim. Acclaim, of course, means access to money, which then becomes time.

This is, of course, a kind of exaggeration, at least to me—I have many things (not a mink, not a Lexus, not a mansion, but like, nice things), which I love dearly, and also a shared life, with someone I love, that also necessitates the accumulation of things I would not sell for more time, compromises where love and practicality and stability have won over the quest for a spare hour, but I know and understand that hunger for time, for quiet, for pushing things aside in this pursuit to just for one minute, shut the world down. He’s also right that every time I have gotten even a shred of acclaim, there’s always the hope that this is the thing that will break me through, that will make everything else I want to do possible, that I never again have to think about my material needs. When I went to the Whiting Awards ceremony a few years ago, the morning after the party many of us sat around in the hotel’s coffee shop, exchanging kind of relieved gasps at how much this acclaim, this money, this time opened up for us.

The second part of the gift is, of course, To Kill a Mockingbird. A classic of modern American literature, the kind of shining novel most writers can only dream of writing, one that Lee barely dreamt of writing herself. Lee signed with her agent in November of 1956, got the gift in December of 1956, and by spring of 1957, after a frenzy of writing (up to 50 pages a week, for several weeks in a row) had a completed manuscript that her agent sold before the end of the year. Just a few short months of funding made time for writing, for the sale of a manuscript, which led itself to an advance, which in turn led to yet more time to work on and refine the book. We know now, because of the contested, (and in my opinion, unethical) publication of Go Set a Watchman that To Kill a Mockingbird was not always the book it became—that Lee’s original vision for this story was one not of racial reckoning in a town but of racial reckoning within our families, of what it means to discover that the people we love are hardly people to look up to (I do wonder how a more polished version of that book would have fared in 1960s America, how its similar success would have changed the way we talk about race while also knowing that a more complex book, one without a hero, would not have fared nearly as well.) The lesson here being that Lee’s original draft was so thoroughly reworked that it could eventually be published as a completely separate book some 50 years later.

And then, To Kill a Mockingbird—a success so wild, so flagrant, so everything that Harper Lee never again needed to worry even for one solid second about her material needs, that took her on a semi-painful publicity tour and led her to become friends with Gregory Peck, even as she nearly lost her friendship with Truman Capote. This success wasn’t unmixed—Lee never again wrote another book, and instead retreated to a kind of hermitism, refusing interviews and further publicity, bitching grandly about her taxes (a pastime I also enjoy, freelancer taxes are the pits), and refusing to talk about past and current writing with many people. Her post-Mockingbird output consisted of 3 short essays (including the one where she describes her marvelous gift), 2 profiles as a favor to Truman Capote around the publication of In Cold Blood, a satirical recipe, and maybe a handful of other short pieces and lectures.

Casey Cep’s incredible book Furious Hours: Murder, Fraud and the Last Trial of Harper Lee is an account of the only other book Lee ever tried to write, a journalistic account of a serial murderer in Alabama. Lee struggled mightily with the book for years, wrote and rewrote chapters, fussed with changes, interviewed locals, paid out $1000 (the same as her advance for Mockingbird) for a trial transcript. In other words, she worked on it, she labored over it, but she never finished it. Cep provides a few different alternatives for why this is—difficulty wrestling a complex real-life story onto the page, an over-reliance on alcohol, too many notes and sources and threads to tug on, but I think the one that resonates with me the most comes from a note Lee wrote to Gregory Peck. Here it is as cited by Cep:

With her first novel, she told Peck, “nobody cared when I was writing it; now it seems that my neck is being breathed on, but I refuse to let this thing go until it approaches some standard of excellence.” Her new mockingbird was starting to seem more like an albatross, and it weighed on her more heavily the more people knew about her work: “My agent wants pure gore and autopsies, my publisher wants another best-seller, and I want a clear conscience, in that I haven’t defrauded the reader.”

Now, I don’t mean to really compare myself to Harper Lee, nor am I working on anything even close to a true-crime-y kind of book, but this feeling of stuck-ness, of audience, of not feeling like the person who wrote the first book, of not wanting to defraud people is one that is sticking with me.

I don’t know that I wrote Rivermouth particularly fast, or particularly intensely (I certainly have literally never, even once in my life, had a 50-page week) but, as wild as it sounds, I don’t really remember writing it. I remember being kind of pleased as it was coming, having the feeling on really working on A Book, I have photo evidence of my index card piles and notes in my journals, but like, I don’t know how it happened. It’s also, somehow been about five years since I finished a first draft of the book.

I was having drinks with Laura Marris over the summer, when she was mid-book tour for her incredible essay collection The Age of Loneliness—her debut. She had that kind of half-dazed, half thrilled look I am sure I had on my face for my book tour, and another author was telling her that her entire first year post-pub would be kind of unreal. Book tour is unreal, and then you get home and you end up processing feelings about book tour for about a year and that’s unreal, and unreal emails and invitations will sometimes show up in your inbox as a consequence of this, and the whole time you’re also like, getting eggs at the grocery store and trying to get another book off the ground and maybe working a job, and all of those things feel a little less real also, because you’ve got this big cloud of “what the fuck just happened” hanging over you. You need time, and space, to unwrite the book too.

I think part of the mistake of my Year of No Job Just Book was trying to write a book immediately post-pub when I was deeply, profoundly sick of the sound of my own voice and unclear on whether I would ever have another original thought again, but I see now that I had a weird relationship to money and how that came in, and other writers and their successes, and to people who were reading my book, and to people who had or had not reviewed the book, and to the book itself. I am also, let’s be clear, very self-conscious right now of engaging in the kind of self-indulgence that means the sophomore album is all about how hard being famous is. I’m not famous, but I still have this feeling of a lot of people standing between me and the page.

I think the thing that made that Christmas gift so valuable wasn’t just the money itself (although, again, the money did not hurt). It was being ready for it—being brimming with energy and ideas and just actually, truly, not having the time to set them down. It was also this bit, which I’m going to let Lee herself tell you about:

“It’s a fantastic gamble,” I murmured. “It’s such a great risk.”

My friend looked around his living room, at his boys, half buried under a pile of bright Christmas wrapping paper. His eyes sparkled as they met his wife’s, and they exchanged a glance of what seemed to me insufferable smugness. Then he looked at me and said softly; “No, honey. It’s not a risk. It’s a sure thing.”

That insufferable smugness, the certainty in the face of your own doubt, is also the real gift. If that trust, plus an agent who believes in you, and a year’s salary in your pocket is all the wind in your sails when you sit down at your typewriter, you’re going to circumnavigate the fucking world before you hit a doldrums. Harper Lee also eventually knew that your book being public is, if you’ll let me stretch this metaphor a bit more, ballast in the hold. Some of it is good, some of it complicated, some of it bad, but all of it needs to be sorted through, hauled overboard or stored away safely, and all of it weighs you down a little more, makes things just that much more complex.

But these gifts don’t always come in these huge grand financial gestures—it’s my husband taking on a lot of extra household chores (on top of the many he already does) when I’m on deadline, my work giving me a little extra PTO so I can do ~*book stuff*~ and still manage to eventually take a vacation, its my professors in grad school taking on independent studies with me and reading my manuscript and providing feedback when it was 70 disorganized pages in a Google Doc. I think the cost of supporting another full-grown adult for a full year has gone up a shocking amount since 1956 and giving a pal a full year of their salary feels…impossible at this point, much less with two children and living in Manhattan, which Lee’s friends were, but I do think it’s possible to recognize this same kind of energy in more everyday sacrifices, to let these things fill my sails and lighten my load. My work matters to me, and it matters to the people we love. Everything else is so much styrofoam, taking up space but not weighing me down.

Having a job again, particularly an in-person one, makes finding the time and the space to write more complicated, I won’t lie. But I wrote one book like this, sneaking drips and drabs of time whenever I could, going to bed bleary-eyed, and as I stay up late typing out this newsletter, it feels…familiar in the best way. I’m not sitting down to write a book, but I’m making time and space for myself, for this, in a way that feels approachable and friendly. A quiet house, a few carved out minutes in my day. Between that and the fact that I’ve been feeding on new things and old favorites like a whale shark, there’s more coming, and soon.

Reading List

To Kill a Mockingbird Harper Lee

How to Write an Autobiographical Novel Alexander Chee

Furious Hours: Murder, Fraud and the Last Trial of Harper Lee Casey Cep

The Age of Loneliness Laura Marris

Note that I make a small commission from any purchase you make from these links, please do!

Reading/Writing/Lady About Town

Right now I’m reading bell hooks’ All About Love and Agustina Bazterrica’s Tender is the Flesh, so some very different vibes from those two.

My latest Christian Century column is about monasticism, a cabin in Maine with my friends, and a vision of what life could be like. You can find it here.

As always, my book is available in bookstores and online—I think it’s a good tonic for the days ahead, especially with regards to immigration. It’s called Rivermouth: A Chronicle of Language, Faith and Migration, and it’s about my experiences translating for asylum seekers, translation theory, and what we owe to one another. Also, God, kind of.

Also I’m going to be at Tucson Festival of Books in March! My schedule is up, if you want to come hang out/bask in the brilliance of the many incredible writers I’m paneling with, I’d love to see you!

As always, if you liked this email, forward it to a friend, post about it on social media, drop me a note.

So well done. Brave. Noble.

Thanks for teaching us.🌱🌎💙