Hello again. I’m working on figuring out a more sustainable, helpful way for me to send out this letter that should hopefully launch in the new year, and it will likely be one that deals with the challenges and horrors that the new year brings, but for now, there is nothing to react to, nothing specific to prepare for beyond the promised horrors, and so instead, I wanted to make a little space for something else.

If there’s something I learned in the first Trump administration, it’s that it can and will be all-encompassing if you let it, and there has to be room for art and beauty and the rest of it. This is not to say that I’m not angry, despairing, grief-stricken, but just that I think there’s a difference between preparing for bad things and giving them space in your brain and your life before they arrive. This is the time to donate some money, to go to a meeting, to have conversations with your loved ones—it is not yet the time to pull focus and fight this particular evil. Fight other evils, save your energy for when it counts, spend these next precious few months filling your tanks and finding your people again. And on the subject of finding people:

Over a year ago now, on another platform, I wrote a newsletter on Emma Craufurd, the translator for Simone Weil’s first publications in English. It starts like this:

“I've had a version of this essay kicking around in my head for quite some time now. That version of the essay is, to be quite humble about it, a masterpiece of archival research, one of those triumphant excavations of a long-lost literary figure, pulling a life out of some forgotten margin and into a well-deserved limelight. The figure in question here is Emma Craufurd, the English-language translator of two of Simone Weil's best and most accessible (?) works: Waiting for God and Gravity and Grace.”

Humble, I know. Even more humble, is that, in the last few months, I have actually written that version of the essay, or at least one that goes much farther than I could for a newsletter. I wrote it for Commonweal, for their 100th anniversary issue, which is its own pleasure and honor.

Despite not publishing all that much, I do feel some kind of bashfulness around writing an entire newsletter just to point out that I wrote an article that got published somewhere else, and I probably wouldn’t be writing this newsletter if I didn’t feel, to some degree, that writing this essay changed me. Let me explain.

I’ve spent the last year in the swamp of writers’ block, just ramming my head against my own dry well, my own determination to write a book I don’t think I actually wanted to write, as evidenced by the fact that I have not written even a single word of it. I was “freelancing,” which is to say, sitting in my home office, hanging up a new piece of art in a Goodwill frame at a rate of approximately one a week until my office looked like a deranged 18th century gallery (yessss) and drowning under admin labor and assignments that weren’t paying enough, but then also making a ton of time to read things that I felt like I was supposed to read but did not, in any way, make me feel anything, and instead feeling the whole time as if I ought to feel lucky or at least productive.

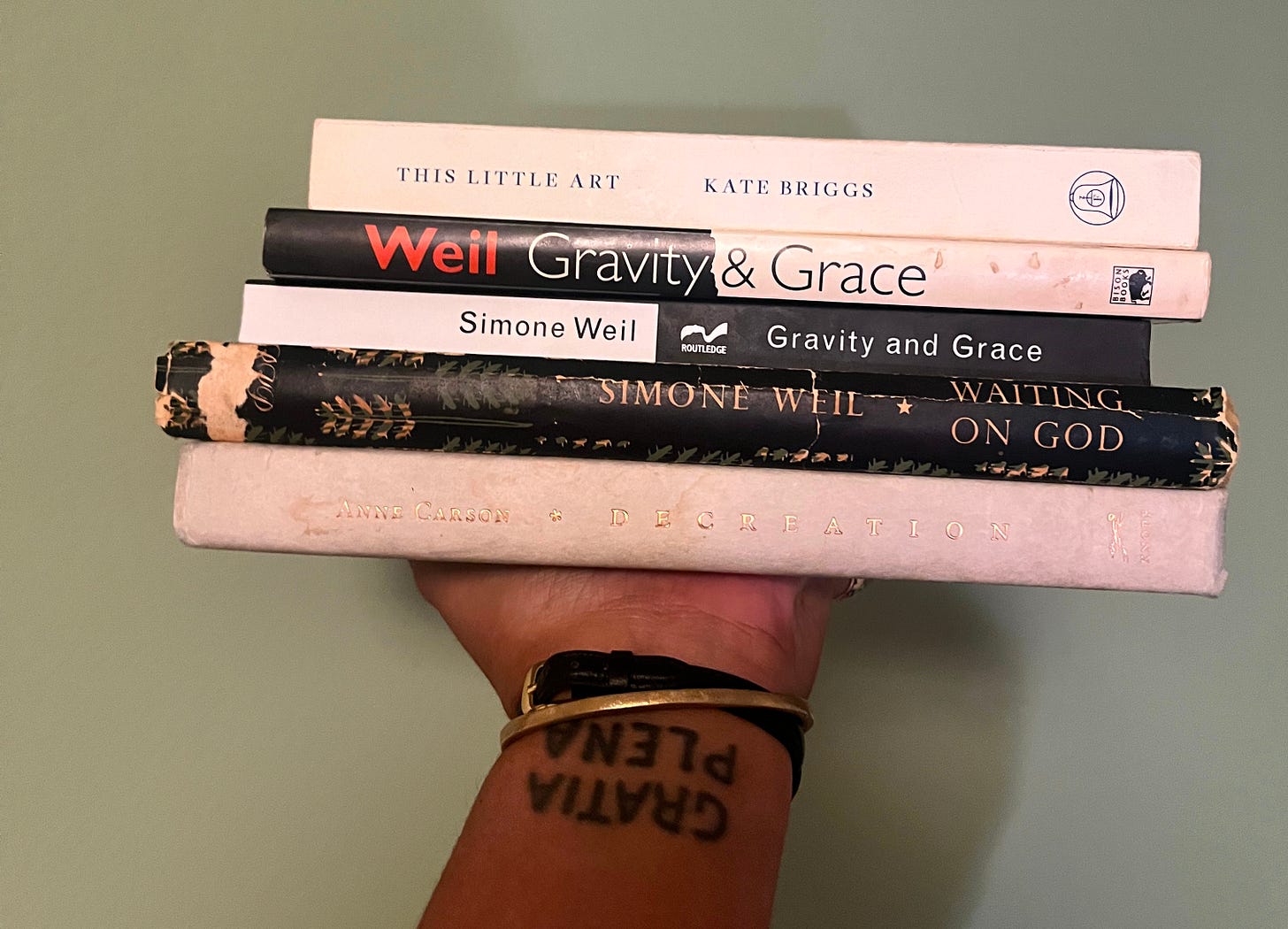

And so when my editor at Commonweal reached out and asked me for a piece, I said yes, and pitched this biographical exploration that I had sorta-kinda-wanted to write for a couple of years, and just kind of gave myself permission to go all-in on it—to do the research I wanted, to spend a little cash in doing research, to just…do it, to write the piece I wanted to write. And in doing so, I spent some time with these books that had meant a tremendous amount to me in graduate school and while working on Rivermouth, with books that had, critically already inspired in me a book.

And as it turns out, that was all I really needed to set me off to the races. Between Weil’s strange, oblique prose and Anne Carson’s blunt, equally strange prose, and Brigg’s winding, meditative sentences I found the stuff I’d been looking for during the past year, and the ideas, again, set my hair on fire. I realized I’d spent the last year reading inert stuff, things that meant well but were more interested in explaining or teaching or treating the reader like an earnest undergrad rather than someone who was there to fuck around with new ideas, to follow the writer into experiment or strangeness or brightness. As it turns out, I needed the latter far more than the former, a kind of writing that was not tight, that did not gather in the ends but that led me instead down a thousand productive rabbit holes. And for this essay, that was exactly what I needed. Well, that and the archival research.

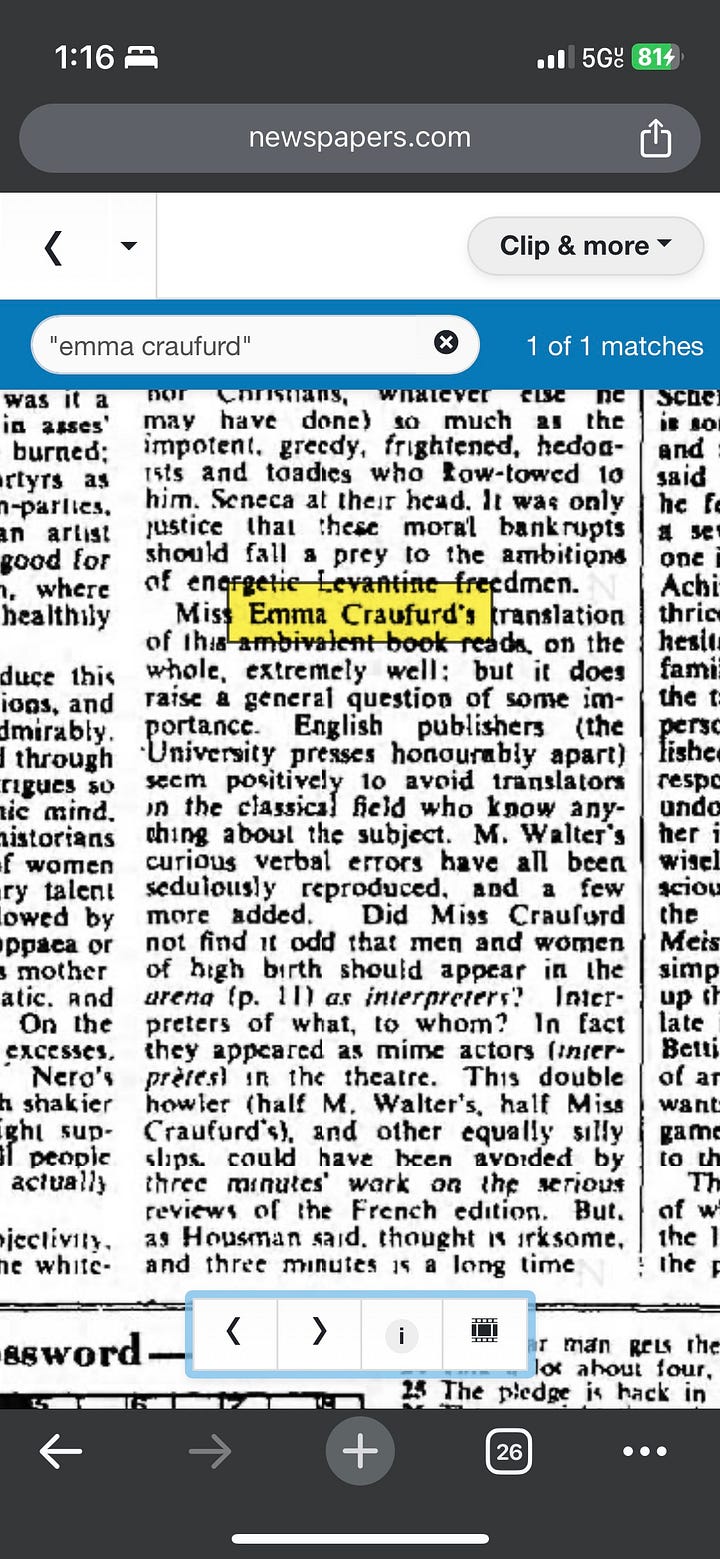

The archives ended up being the best and worst parts of this project. I started with ancestry.com, working forwards on her family tree to see if, possibly, I could find someone who remembered her who was still alive—a grandchild, a niece, a nephew. She does have a living nephew, a baronet in his late 80s. I couldn't figure out how to get in touch, or if he'd remember a spinster aunt well enough to be worth it. From there it was trying to track down the kinds of relics that live on newspapers.com: obituaries (no dice), essays, interviews, notes that she attended the village jam contest, anything. I'm not an expert in this kind of research, no better than anyone who has spent some time on Google.com, but it still felt strange, that a woman who had died in 1967—a year during which my own father was alive!—and had by all accounts a vibrant career working with some of the key texts of the century could now be basically vanished.

But where it got weirder was when I compared the extant two translations of Gravity and Grace in English. Basically: I decided to compare the Craufurd and the Wills translations to see how they held up against each other. They were…word-for-word identical, no matter what page or section or passage I opened both books up to. No variation. This, for those of you who don't translate, is about as likely as TWO monkeys on typewriters creating word identical copies of Hamlet. Translations of the same text should in theory be similar, should point back to their identical sources, but there's no way two minds, working in separate spheres, should make identical choices, associations and grammars to produce identical translations. I did end up figuring out that the Craufurd was published before the Wills, making hers the older, “original” translation, but was not able to find which version had, theoretically, overwritten the other.

This was largely because when I tried to chase down an older, pre 2004-reissue-edition of the Craufurd (mostly because I suspected my own copy of a certain kind of fishiness due to wonky spacings and Craufurd being rendered as “Crawford” on the title page,) all the old versions were lost or missing from their institutional libraries, lost to time, or unable to be accessed thanks to a lawsuit against the Internet Archive. I felt conspiratorial, the red yarn and corkboard about to displace all my goodwill frames.

And then my deadline came, and I reached the limit of what I was able to find out about Craufurd in the time I had. I'm proud of that piece as much for what I was able to uncover as for how I was able to talk about what I wasn't, the ways I was able to link Craufurd’s disappearance not just to her own biography but to bigger ideas set out by Weil and Briggs.

So now what? The answer is, once again, trying to write something. But this time, I want to set out from the things that set my hair on fire, the things that light me up, not the things I want to or ought to care about. This was the feeling I’d been chasing all year, and that had eluded me all year

The next book won't be a continued exploration of Craufurd’s life, in part because I suspect I'm at the end of what's possible for a Yank with internet access and no current ability to knock on pensioners’ doors in the UK, but the lessons of this essay and the mysteries it still holds will stay with me for a long time. (Although—if you have insights, clues or ideas about Craufurd or Weil, or you want to pay me money to keep investigating this in a more boots on the ground kind of way OR you want to give me this particular book deal with a massive research budget, GET IN TOUCH).

If you want the turbo-charged version of reading my Commonweal article or are just a regular amount of curious about any of the texts I mentioned, here’s a list of books I read and links to purchase them. I make a small commission if you choose to purchase from these links!

This Little Art, Kate Briggs - a book I recommend so often and with such fervent passion, I ought to just add it to an Ojos de Santa Lucia Best-of List

Gravity and Grace, Simone Weil - Bookshop only carries the Arthur Wills version which is FINE, I GUESS, because it is WORD FOR WORD IDENTICAL to the Craufurd and I do regretfully admit this cover is way better than the weird red balloon Routledge went with BUT it does feel sort of weird to recommend this one given all that you’ve read.

Waiting for God, Simone Weil - probably where I’d start for a Weil newbie, this is also where her essay on attention that I’ve written about several times before lives

Decreation, Anne Carson - I’ve been putting off reading her latest because I love her so much, but this is a classic for a reason

I’ve done a fair bit of publishing in addition to the Craufurd essay, but I think the main thing I want to spotlight is actually this talk I gave as part of Chicago’s Lit and Luz festival. It was about two weeks before the election, but their theme was Saturation/Saturacion, inspired by the feeling of living through an election year in Mexico/the U.S. If you opened this newsletter wanting to hear me think through the election and another 4 years of Trump, I think that this is my answer.

Finally, you may have noticed the newsletter facelift we just got—everyone thank , the incredible author of and an incredible artist in their own right bc now my newsletter looks good. I think my favorite part is the little red thread dangling from the sleeve, a nod to the cover of Rivermouth, which, hey, you should buy if you haven’t yet!