I’m in the midst of a re-read of Rebecca May Johnson’s incredible book, Small Fires: An Epic in the Kitchen. Ostensibly, this began because I wanted to write an essay about it for one of my regular columns at the Christian Century, or at least an essay that glanced off it in some way. I’ve written about Small Fire and feeding The Other before—for Presbyterian Outlook1, in one of my favorite essays2, but this is the first time I’m re-reading since about a year and change ago.

The real reason I think I’m re-reading it is because I’ve been a little disenchanted lately. Part of that is with my reading—in the last 6 weeks or so I have worked through 21 books for CLMP, 35 applications for Chicago’s Individual Artist Program grant, 2 books for a Q&A I’m doing this weekend, and while many of the things I read were incredible, they were also…not really my choice to read, and there was a certain kind of pace I had to hit to get all of it done before the various deadlines. Reading as a(n occasionally joyful) chore. However, the feeling goes beyond that. Lately, I feel a mounting sense of dread any time I have to grocery shop or pick recipes, feeling exasperated and exhausted, idly wondering about crossing the Soylent rubicon. I went to the doctor’s for my annual yesterday and filled out their little depression screening, looked down at it when I was done, and said, “oh, yikes.” Things are weird and bad right now for reasons both internal and external to my life, and it’s time to look for more sources of enchantment.

This week, Small Fires has been that source of enchantment. If you’re not familiar—Rebecca May Johnson brings the tools of literary criticism to bear on the idea of the recipe, and you end up with essays on cooking as performance, as translation (if you’ve ever read anything else I’ve written, you can see the sparks going off in my brain here), as gender, as kink, as play, as negotiation, as care. I’m someone who cooks dinner every night, and I’m also someone who theorizes the everloving shit out of well, everything, and Johnson’s book is an invitation to do just that.

The thing about Small Fires is that it itself feels like a recipe, like an invitation to play. I want to, in Johnson’s own framing (!!!), perform the book in my own kitchen, walk my own food autobiography through the steps of her reasoning, re-examine my own hands and habits under the lenses she provides throughout the book. I want my disenchanted sigh at my refrigerator doors, to be transformed, under her sparkling vision, to a questioning head tilt—what is the source of my dread, why do I need to feel enchanted with myself as a home cook? I want to think about the chilaquiles I’ve made since college in the same way she does the red, hot pasta sauce that threads its ways through the chapters of the book.

Back in grad school, I wrote an essay about the eucharist as a translation. The very origins of the practice are “translated” four times, once through the eyes of each of the four evangelists. It’s every repetition is a translation, with all the same holes and bagginess through which meaning escapes and enters the translation of any text—the “misfires” as Amy Hollywood puts it, through which possibility and play enter the ritual. Into this essay I brought Annie Dillard (“Expedition to the Pole”) and Anne Carson (Decreation)—in other words, I made it my own, populated it with my own greatest loves. I wanted, in it, to suggest that the eucharist, like a translation, was both a site of grave importance and a site of play, that the Holy Mysteries of what happened at the altar were subject to other, very earthly mysteries. In the words of Annie Dillard: “A high school play is more polished than this service we have been rehearsing since the year one… Week after week, we witness the same miracle: that God is so mighty he can stifle his own laughter.” I got a B on it, largely because my theology was bad, but I still think of it often as an essay in which I wrote a true thing that I believe, which is to say: that real life is holy, and playful, and that mistakes and refusals and misfires, that the reality of our human bodies engaged in these holy mysteries—this is what allow that holiness to come through, rather than blocking it.

I think Small Fires more than anything, reminds me that the things that we do every day are worthy of the most attention, that our hands among ingredients and among our friends change the world and our tastes every day. It’s one of the first books I’ve really read that affirms this idea, that honors the desire and the hunger of the everyday.

Where I’ll Be:

Tomorrow is a doozy!

April 26th, I’ll be moderating an event with the INCREDIBLE Marcelo Hernandez Castillo at Chicago Public Library—he’s keynoting their Poetry Festival, and I’m just lucky I get to yap with him.

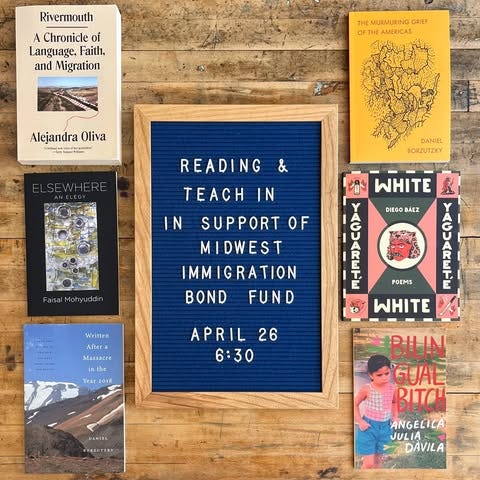

Also April 26th! I’m taking part in a reading and teach in to support my beloved Midwest Immigration Bond Fund at the incredible Pilsen Community Books—come thru, buy posters, buy prints, spend a little cash!

May 1st, I’m going back to the old stomping grounds of Harvard Divinity School for the Peter J. Gomes, STB ’68 Distinguished Alumni Honors. I’m one of the honorees this year, which has me absolutely geeking out, but I think there will be a public component to the program that you can sign up for.

What I’ve Written

I wrote a Lenten reflection for Commonweal about losing faith in institutions to protect us and finding a new way forward.

I wrote a review of We Are Green and Trembling for Americas Quarterly—it’s the story of a former Spanish nun turned swashbuckler in the New World—a really beautiful weird story that nevertheless glosses over some historical issues that deserve a little more consideration.

And finally, for Injustice Report—I wrote about Necrocapitalism and the immigration system—a consideration of the remarks and actions of the administration from the last week or so.

We are going to talk about my beautiful publishing niche as a writer with Raised-Evangelical-In-Texas religious trauma who is somehow making a career out of writing exclusively for Lefty Christian Magazines some other time, but for now, yeah, wow, that is…present.

Is it weird to say that about something I’ve written? I don’t really care, it is.

Have you read Tish Harrison Warren's book Liturgy of the Ordinary? Super aligned with the penultimate paragraph comment on real life being holy and playful.